Extensive Resilience Program for Residential Counselors Launched in 40 Facilities Across the Country

November 24, 2025Often when asked what I do for a living, I will respond “I make Upstanders.” This is usually met with “But how do you know?” In 2007, I created a curriculum on the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s for 5th grade. The goal of my curriculum was that my students would know “what the world looks like when it is going terribly wrong” and that they should do something if they see it happening. In 2008 at a Facing History and Ourselves (FHAO) seminar I learned a word for what I was asking my students to become, Upstanders. Usage of this word can be traced to Samantha Power in 2003 in connection to her book on genocide as she discussed those who spoke out against the Holocaust and Armenian genocide. You can read more about the word here on FHAO’s website.

I brought this word back to The Jewish Day School of Seattle (JDS) where I have taught for the past 21 years. At JDS, this word spread from my classroom to the wider community and is now integral to JDS’s Mission, which reads: “JDS empowers children to grow into capable, wise, and compassionate upstanders by integrating an innovative academic program with Jewish education and traditions.”

But how do I know? I have anecdotal evidence: the student who wanted to make “the film to end genocide” and created a documentary about the Rwandan genocide, the student who went to India to help improve educational opportunities for the poor, students who spoke up to school boards after 10/7 about the antisemitism they were facing. But is this enough to really know?

As part of my course work in the Mandel Teacher Educator Institute (MTEI)/Hebrew Union College Graduate Certificate in Educational Leadership, I was asked to research my own practice as a teacher. I immediately knew my research topic! Does learning in my classroom empower young people to be Upstanders? If so, what experiences in my Jewish Studies classes and, at JDS in general, contribute to this? How does a JDS education show up in our alumni and their life choices?

To prepare, I read three articles to see how others have researched this question. While the educational settings were different from mine (a college classroom, a summer seminar and a public school), all used familiar instructional methods. They used stories and role models to inspire their students and generate discussion about what it means to be an Upstander. While these articles did not clarify a methodology, it was reassuring to see their successes.

My inquiry was guided by the Structured Ethical Reflection approach, as outlined by Stevens, Brydon-Miller and Raider-Roth (2016) in The Educational Forum. I selected values to guide each step of my research. Knowing that I was researching myself and my impact on students, I felt it was important to keep humility, objectivity and transparency at the center of my methodology and analysis. I wanted to be inclusive of as many voices as possible and curious about the true impact of time in my classroom and at JDS. All of these values were reflected in each step of my planning and research to assure that my findings would be valid and honestly reflect the input of my participants. I checked in with my participants after analyzing the data to verify that their input was properly interpreted in my findings. They confirmed that it was and found it powerful to see their experiences reflected by others as well.

My primary research tool was a Google survey that was sent to graduates from the classes of 2011 through 2025. My main research query was:

What experiences during your middle school years at JDS do you continue to tap into for inspiration for being an Upstander in your life? What choices have you made in life because of these experiences and the values learned from them?

However, I did not ask these questions directly. It was important for me to know exactly how respondents defined “Upstander” and how they present as one in their lives, so they were first asked to define this word. Next, they indicated the degree to which they agreed that “JDS had a significant impact on my understanding of the importance of being an Upstander.” Their rating of fourteen experiences from across three years of Jewish history, Tanakh and rabbinics for how much of an impact each one had on their development as an Upstander allowed me to see what experiences were formative. In addition, respondents had an opportunity to share their thoughts on the listed lessons, other Jewish learning that I had not listed, and general studies experiences that had been formative. My goal was 25 responses, and I was thrilled to receive 32. I also did six interviews.

So, what did I learn? I learned that JDS does make Upstanders. All responses to the core prompt “JDS had a significant impact on my understanding of the importance of being an Upstander” were in the positive range, with 71.9% agreeing strongly with this statement. I learned that lessons and activities that allowed students to take a deep dive into the story of one inspiring person had the strongest and most lasting impact on their awareness and confidence in being an Upstander. Respondents reflected about the impact of learning in depth about a Jewish partisan, writing their own historical narrative as a young Jewish person in Germany in the 1930s, learning about morally courageous people, and the Righteous Among the Nations. Connecting in a meaningful way to the stories of inspiring and brave people, who stood up for what was right at risk of their lives, helped my students see the difference one person could make, that even young people can make a difference, and that we never know what we are capable of until we have to.

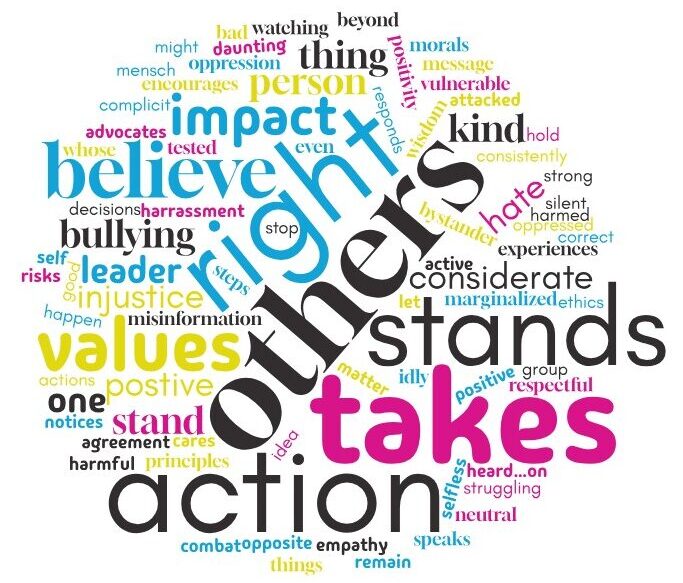

Word Art of the 32 definitions of Upstander

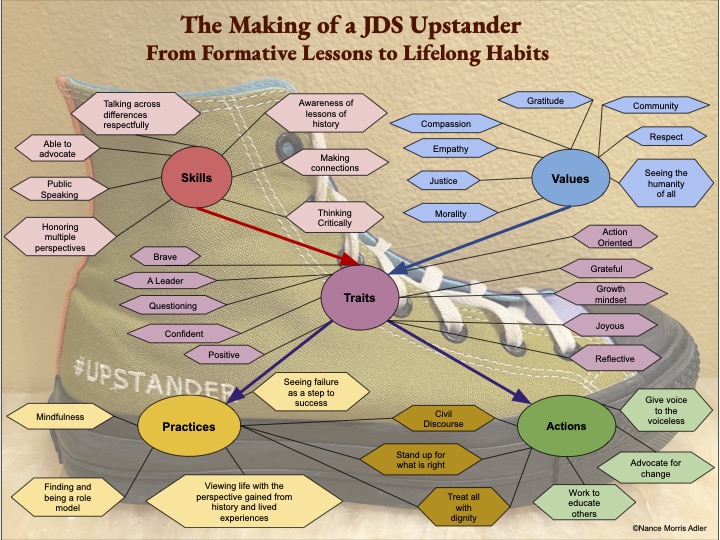

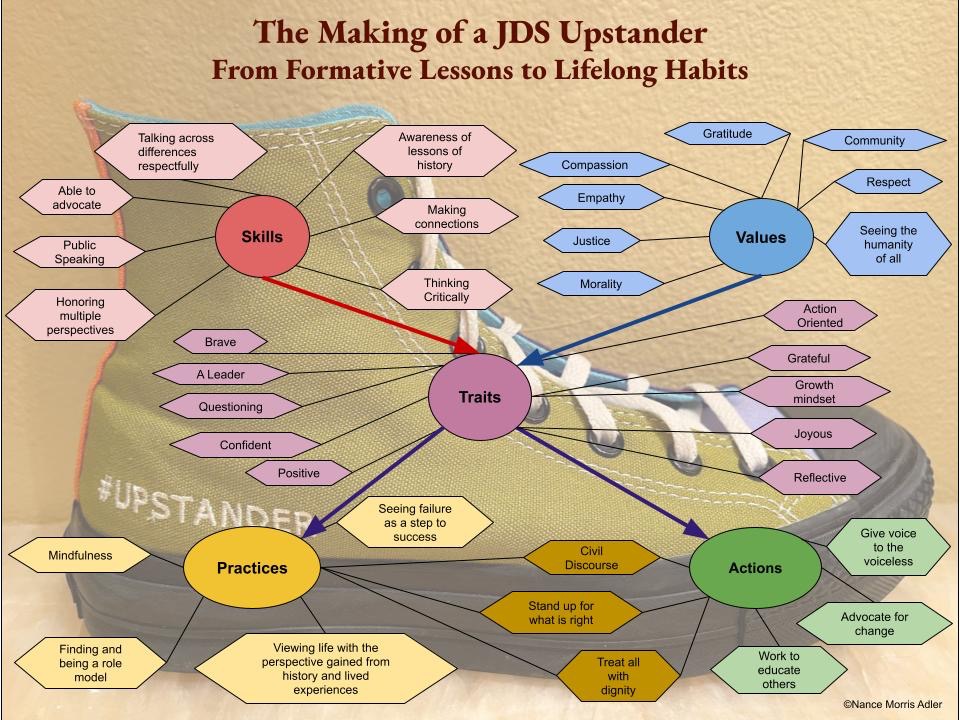

From the 32 definitions of the word Upstander, as well as from the interviews and free responses, I was able to compile a list of “habits of mind and practice of Upstanders.” This list was then organized into the graphic below which shows the skills and values JDS students learn in their Jewish Studies classes that in turn become character traits. Graduates found that having this foundation allows them to have the daily practices necessary to take action when they see a wrong in the world. Practices are different from actions in that they are regular habits, or ways of thinking, which then contribute to the knowledge that action is needed, and the ability to take it. Skills such as critical thinking, knowing the lessons of history, and the ability to hold multiple perspectives and speak across differences are taught implicitly and explicitly in the lessons in my classroom across three years. Values, both Jewish and universal, like seeing the humanity of all, community, empathy, compassion, gratitude and morality are modeled and taught across their years at JDS. These work together to instill traits that result in confident young people who can speak up and who ask questions and are reflective. These Upstanders allow the joy and gratitude they feel in their own lives to feed their knowledge that it is their job to help others who are not so privileged. In their daily lives they are mindful and use their awareness of history to make connections to what is going on around them and to see where change is needed. They take action, they speak up and give voice to the voiceless, they advocate and educate for change.

Diagram of how JDS creates Upstanders based on my research

As importantly, I learned that lessons I had not included, like the God Talk series in my 8th grade Theology course, are also hugely formative. This speaker program, which I viewed as a comparative religion experience, is seen by my former students as key in their development as Upstanders and many expressed their surprise that it was not included in the listed units. Yael’s comment states it most strongly:

Besides teaching about other religions, G-d Talks allow us to empathize and understand other religions, creating a general environment of tolerance and open conversation. When one learns from a young age that engaging in difficult conversations (like those surrounding religion) are not only allowed but encouraged, one feels more comfortable pursuing those throughout one’s life. When you fundamentally understand that even people who disagree with you are human, you are drawn to stand against hate/oppression towards any person or group of people.

As a result of my research, I have already added new learning goals for this program that makes clear these skills are not a side product, but a desired outcome.

Seeing the impact of my teaching over the past 18 years has been humbling and deeply rewarding. I presented my work to my fellow MTEI Cohort 11 members in October, and was moved to tears by their responses to my work. One comment that really stuck with me was about how “vulnerable” I was able to be in asking these questions. This connects to the values of curiosity and honesty I included in my Structured Ethical Reflection and really being open to whatever the answers might have been to my questions. Doing this practitioner action research project provided me with data about the impact of my teaching, and enabled me to visualize the outcomes of what I teach in a way that enables me to strengthen my own teaching, as well as create workshops to educate other teachers. I shared my findings with the faculty at my own school during our fall orientation week and am working to help other teachers bring more of these valuable lessons into their classrooms. My school will be using my findings to help create a “Portrait of a JDS Graduate” that incorporates this real world data that shows what our graduates already look like. Having transferable and replicable outcomes that can be shared with other teachers allows me to help others create more Upstanders…something our world sorely needs.

Nance Morris Adler is the middle school Judaics instructor at The Jewish Day School of Seattle. She is also the Mashgiah Ruhani and middle school co-coordinator. Nance was part of Cohort 11 of the Mandel Teacher Educator Institute and completed a graduate certificate in Education Leadership as an additional part of this two year fellowship. This research was her coursework for that certificate program. Nance was awarded the Rabbi Dr. William H. Greenberg Z”L Master Teacher Award by The Samis Foundation in 2020 and is grateful for their ongoing support of her professional development.