Day School Alumni Spotlight: Benjamin Cape

October 15, 2021

Samis Trustee Spotlight: Eli Almo

October 29, 2021

What is education for if it doesn’t make you a wiser, better person? Local day schools work on creating a “culture of kindness.”

By Emily Alhadeff

In 1930, Jewish education scholar Shlomo Bardin gave a lecture to the Columbia University Faculty Club, where he shared a critique about the American tendency to “measure” academic success rather than allow students to process, analyze, and reflect — in other words, to search for meaning. To this day, academic success hinges on metrics: test scores, grades, GPA.

Still, the US ranks squarely in the middle of the pack when it comes to math, literacy, and science as compared to other industrialized nations. Our metrics for academic success, it seems, have failed to close the achievement gap, while at the same time they push high-achieving students to the brink of a nervous breakdown.

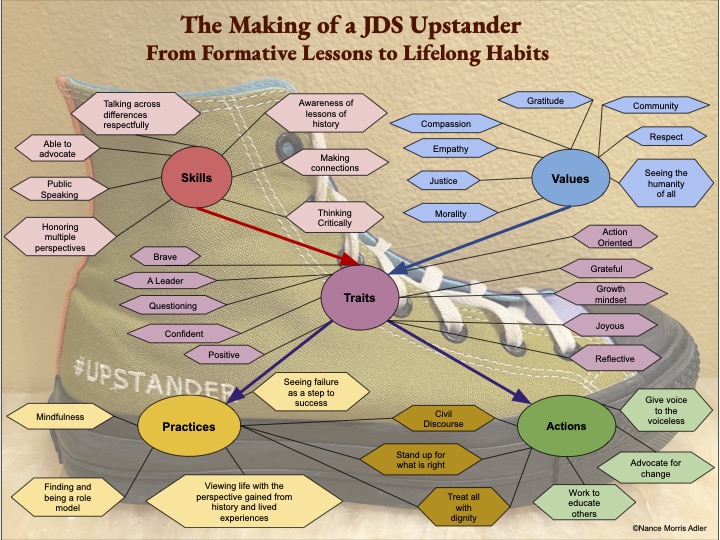

In their book Raising A+ Human Beings, veteran Jewish educators Drs. Bruce Powell and Ron Wolfson advocate for a shift in attention away from AP competition toward “AP kindness.” By creating a school culture of uplift, inclusiveness, and inquiry, Jewish day schools can produce humans who are not just academically excellent, but also the embodiment of Jewish values in their attitude and quest for meaning.

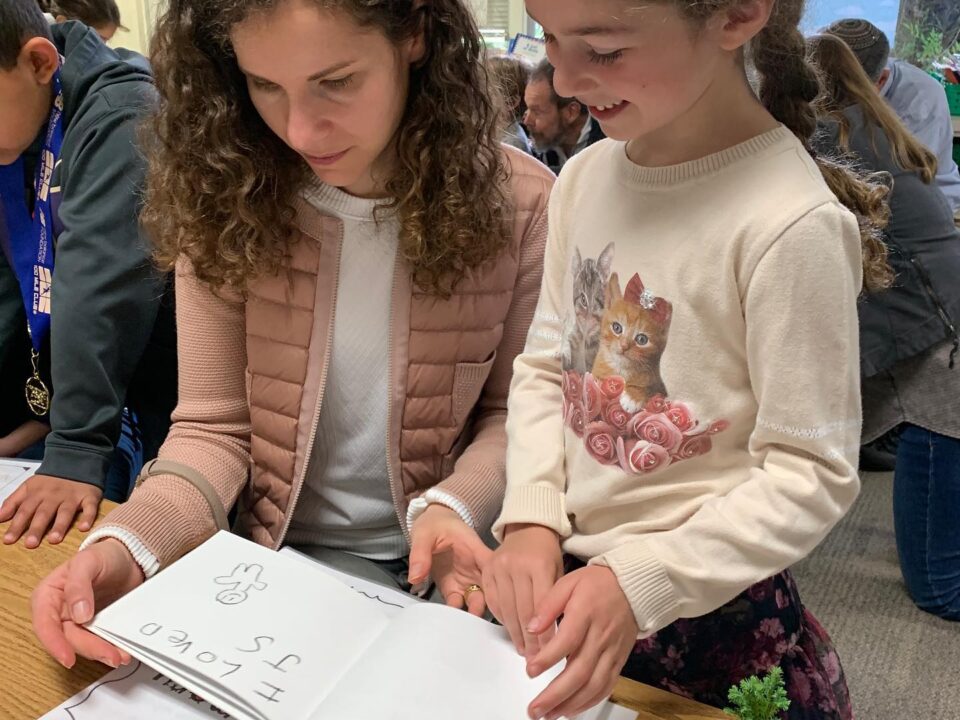

Recently, every parent in the Greater Seattle day school system received a copy of Raising A+ Human Beings courtesy of the Samis Foundation, which supports day schools and Jewish education initiatives in Washington State. The community-wide “book club,” complete with webinars for teachers, administrators, and parents, intends to get all the day school stakeholders on the same page about the value of a Jewish day school education — namely, that it’s not just about academics, but about building character.

“With parents who have kids in day schools, you’re preaching to the choir, but you have to make this recommitment to investing in the education,” says Melissa Rivkin, director of day school strategy at Samis. After seeing Wolfson and Powell promote their book last spring, various administrators and Samis trustees got excited about the possibility that “this could be a topic that will resonate with every parent — not just day school parents, but future day school parents,” Rivkin says.

It turned out that many administrators and teachers were already familiar with Powell and Wolfson. Wolfson is a professor of Jewish education at American Jewish University in Los Angeles; Powell is credited with running Los Angeles’s de Toledo High School and pioneering a model of healthy school culture. Their book is the result of Wolfson’s urging Powell to sit down and write what he calls “the Torah of Bruce.”

“Bruce was involved in a mentorship program for heads of school. He was my mentor, which was like hitting the jackpot,” says Seattle Jewish Community School head David Zimand. (Zimand even has a cameo in the book.) Zimand took the helm at SJCS, in North Seattle, this summer and is aware of the attrition crisis facing day schools over the past couple of decades. “Covid of course has been terrible,” he says, “but a silver lining is it re-centered all of us. In some ways, it shined a light on what day schools do well.”

That thing, according to Zimand, is nurturing the soul as well as the mind. “Ron and Bruce’s book is such a beautiful expression of the timeless values of our people and the way we think of education,” he says. “It’s not about the pursuit of knowledge in and of itself; it’s about the pursuit of wisdom. Too often, education becomes this false dichotomy.”

How can a school engender a culture of kindness and curiosity, and how can a school turn a toxic culture around? Powell and Wolfson outline the what, the who, and the how of internalizing a positive school culture and values. It requires everyone to be in on the plan, from administrators to grandparents, donors to maintenance staff, and obviously teachers and students. The change starts with language and relationships — simple-sounding techniques that in fact can have a big effect.

For instance, to break up cliques, school communities can shift to the language of “a circle of friends.” Recognizing a circle of friends as opposed to isolating a best friend “takes a tremendous pressure off the kids,” says Torah Day School head Rabbi Yona Margolese, who also counts Powell as his mentor. Culture exists, whether it’s intentional or unintentional. To instill a “culture of kindness,” Margolese ensures that every new hire to the Beacon Hill K-8 school exemplifies the school’s values. “One of the things I’m most proud of [is that] we don’t have any yellers in the building. We have no teachers who yell at the kids,” he says. “It becomes the main part of the curriculum, even though it’s not written down anywhere. I don’t have a sign on any wall of the building [saying], ‘It’s hurtful to insult someone else.’”

At times, Powell and Wolfson’s anecdotes come across as almost Pollyanna-ish, a grandfatherly, outdated approach to life in the age of Instagram, TikTok, partisanship, and a pandemic. How does one implement a culture of “AP kindness” in the face of such forces? Is it realistic to expect a teenage student body to give up lashon hara, for strong-willed parents and opinionated donors not to get their way, or for seventh graders to reimagine themselves as a circle of friends? Culture change inevitably starts at the top, requiring significant investment on the part of administrators.

Zimand points out that creating a culture of kindness is easier in the elementary schools, where good behavior is basically part of the pedagogy. The stakes get raised in high school, when AP classes do matter and college admissions are more competitive than ever before. Jason Feld, Northwest Yeshiva High School’s head of school, believes focusing on AP kindness can supplement strong academics.

He points to their recent “reverse Tashlich” event cleaning up litter along beach as an example of living school values. “It was a way for the school community to come together and say, ‘This is something that is important to us, and we have agency and an opportunity to do something about it.’ And so for a few hours, we made that little stretch of a waterfront more beautiful and more environmentally sound,” he says. “The main goal for me is that it becomes an important part of the school’s culture. When you come here, it isn’t just about academic excellence, although we do take that seriously. But above all of that, are we the best? Are we the best people we could be at any given moment?”

“To me, the book is not saying we shouldn’t care about [academic excellence], but these are not the only things,” Rivkin says. “If you’re so laser focused on the colleges and you can get into and which AP classes you can take, that’s really sad. We already know that it’s much bigger than academics. Not all of you will be A-plus chemistry students, but you can all be A-plus human beings. As kids get older, we can lose sight of that. For some parents and families and even the kids themselves…their GPA defines who they are as people. We know as Jews that’s not how it should be.”

Margolese takes it a step further: A healthy Jewish education benefits Judaism as a whole. “Today’s generation of Jews are just lacking a tremendous amount of confidence in who they are,” he says. “There’s so much depth and richness to Judaism. If people just knew, they would be able to walk down the street with their head up high….The more intentional our day schools could be about creating that culture in our schools, the more successful we’ll be as a Jewish people.”

In their book, Wolfson and Powell reflect on Shlomo Bardin’s 1930 speech about measurement versus meaning. What is all this education for, if it doesn’t make you a wiser, better person? “And we wonder why schools are failing,” they write. “We wonder why students become bored with their studies. We wonder why testing is simply not working to promote real achievement.”

“We’ve become so focused on a very narrow understanding of accomplishment, of learning, of growth, of what notches we need on the belt. Education wasn’t about admission to the next yeshiva; it was about pursing wisdom, making the world a better place,” Zimand says. “I’ve spent the last 15 years wanting to holler this from the rooftops.”

Originally published on October 15, 2021 in The Cholent: https://bit.ly/3lZ188x